I was recently honoured to join a panel hosted by Diana Tedoldi and Ellen Zimmerman for the ICF’s Executive & Leadership Community of Practice. The topic was wellbeing.

Also on the panel was Ram Ramanathan and Giulio Brunini – both master coaches with a huge depth of knowledge and experience.

In preparation for my contributions, which included a meditation on awe in nature, I wrote the following paper. I thought you might like to read it.

Introduction

Let us start with a hypothesis: ‘No good life without nature’. To explore whether this might be true, let us examine what is ‘nature’, what is ’without’, and what indeed is ‘good’? We will then look at the benefits, and cultivating the practice.

What is ‘nature’?

‘Everyone needs Nature’ is an easy thing to say. But what is nature?

Perhaps better is ‘ecology’ – the systems that support planetary processes and lifeforms. Lifeforms including ‘humankind’ (as philosopher Tim Morton puts it), and other ‘non-human people’ or ‘earthlings’. Nature is a form of othering. A shorthand with origins in the neolithic, when we built the first villages and the walls that separated ‘us’ from the wild ‘them’.

Today these walls are taller and stronger – literally and metaphorically. We have parcelled up and designated nature reserves and green spaces as islands in the wider landscape. We visit these places, and then retreat again into our offices, living rooms and virtual environments. We watch nature on TV – or not at all. And other earthlings are disappearing fast – for example, there are 73 million fewer birds in the skies of Great Britain than when I was born in 1970 (BTO, 2023).

What are we not ‘with’, if we are ‘without’ nature?

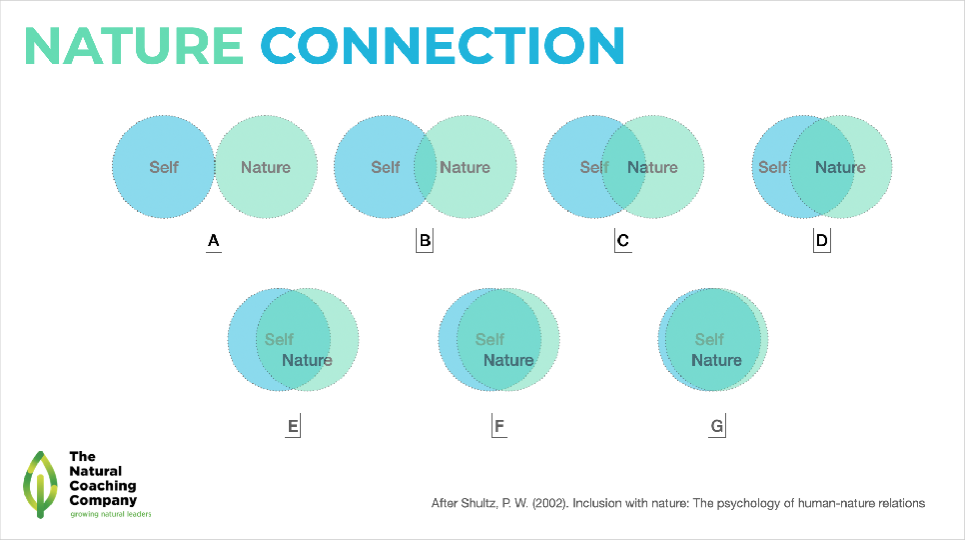

Being ‘without nature’ is still a kind of relationship with the living planet, but one which is contrarian and exclusive. The inverse is to be inclusive and I find it helpful to think of the overlapping circles that the Professor of Psychological Science P Wesley Shultz calls ‘inclusion with nature’. These circles pose the question, To what extent does your identity – an an individual representative of humankind – overlap with other earthlings?

Of course, individuals, communities and societies vary in their degree of inclusion or exclusion. The UK is known to be one of the most depleted countries in the world in terms of wildlife – and has also been judged to be one of the least nature-connected (Richardson et al, 2022). The two are connected – perhaps unsurprisingly, our own work at The Human Nature Partnership has shown higher levels of ‘nature connection’ amongst NHS staff working across the county of Kent in England than colleagues in an inner city London hospital with little surrounding green space.

Those who are ‘without’ are less likely to feel a sense of belonging to the natural world, and may lack an understanding of how their actions affect the natural world. We can measure this with tools such as the Connectedness to Nature Scale (Mayer & Frantz 2004), and the extent to which people engage with the five critical nature connection pathways: Senses, emotions, beauty, meaning and compassion (Lumber R, Richardson M, Sheffield D, 2017).

All this talk of ‘nature connection’ can be a turn-off however. Science rarely finds the right language that grabs us where it matters. So here’s an alternative. I’m a surfer, and in Australia in particular (where I was born), surfers talk about ‘getting amongst it’. There’s a beautiful simplicity for talking about nature connection in such a simple way. “Did you get amongst it today?”

What is a ‘good life’?

There is excellent evidence that humankind cannot live fulfilling, healthy lives unless we ‘get amongst it’ (There is also good evidence that nature can live a perfectly fulfilling, healthy life without humankind in the mix!). The weight of this evidence is mighty.

Put simply, time in and near nature reduces the risk of us dying earlier than we should, or suffering ill health. Numerous studies show how natural environments lower anxiety, stress and blood pressure, induce a sense of calm, and contribute to lower levels of disease and death (Maas et al 2009). There are new discoveries all the time. For example, work in Japan and Korea in the last five years shows that the plant chemicals we are exposed to when ‘forest bathing’ boosts the production of anti-cancer ‘natural killer’ cells in the blood (Cho et al 2017).

Meta-analyses by Pritchard and others (2020) showed that personal growth – a key aspect of eudaimonic wellbeing – has a significantly strong relationship with nature connectedness. In a safe green place, we tend to spend more time looking up and around. Our jaws relax, breath gets quieter, gaze softens and widens, and we orientate to others. Our trust centres open, oxytocin is released, and our ‘vagal tone’ improves. All these responses naturally lead to increased happiness, wellbeing and compassionate and pro-social behaviour. Experiences of ‘natural awe’ actually strengthen our bonds with others and make us more caring (Piff et al 2015, Weinstein et al 2009). Working outdoors can even lead to greater creative thinking and innovation (Plambech & C.Konijnendijk van den Bosch 2015).

As coaches, why wouldn’t we want a taste of this good life? Why wouldn’t we want this for our clients – the leaders and executives that drive cultures and decision making within their organisations. And why wouldn’t they want it for their staff, their customers, their clients?

Good for us all

And there’s more. In turns out that cultivating a deep sense of ‘oneness’ with fellow earthlings is critical for the wellbeing and success of us humans, our human communities, and the natural world In those surfer terms, getting amongst it is good for us all.

Studies have shown that connecting regularly with nature leads to huge health, wellbeing and relationship benefits, as we have seen. But the benefits don’t end there. The kicker is that the more we practice this connection, the more likely we are to exhibit personal behaviours that are good for the planet. Studies have demonstrated double the pro-environmental and pro-nature conservation behaviour amongst more nature connected individuals, compared to the less connected.

This matters. Wholesale system change is necessary to adapt to climate change, as well as slow and reverse the trends in catastrophic heating and ecosystem damage we are seeing across the world. This involves the large state institutions, trans-national bodies, and global players – the banks and investors, energy companies and so on. But these bodies and institutions are also comprised of humankind. Leaders, executives, staff who can be influenced.

And there’s the rest of us. According to the UN, you and me can make a difference. The actions within our individual gift are considered to make up over a third of those necessary to keep runaway climate change at bay (UNEP & IUCN, 2021).

So a surprising benefit is that by getting humankind in touch with other earthlings, all earthlings may be better off. At least you might agree that the chance of us all being better off diminishes if we don’t get amongst it – or have an ‘it’ to get amongst.

Cultivating our practice

We have a responsibility to nurture our own practice, and like anything, nature connection can be grown with practice. You will find what works from you – simply following the pathways of your senses and emotions; reflecting on what is beautify and meaningful about the natural world to you; and how you could show your compassion.

Here is one practice you could try, from our book ‘Being in Nature’.

’Be Kind’ is a short, self-guided reflection to conduct in a safe, comfortable, natural green space. The focus is on thinking kind thoughts about the natural world you are observing.

Asking what you notice in nature, and yourself as you do so. Reflecting on what is happening to your emotional state and the compassion you feel for the natural world. It can be coupled with a somatic exercise, opening the chest and arms, and lifting the gaze.

“Think kind thoughts about the natural world you are observing. Notice the clean air you are breathing, beautiful colours and movement, the gifts that nature brings. Notice a sense of calmness and connection. What else is happening to your emotional state? What love and kindness are you feeling, and what is being returned to you?”

The practice activates the vagus nerve, and releases hormones including oxytocin that strengthen feelings of pro-sociality and empathy. Practicing self-reflection in nature builds nature connection more powerfully than mindful or meditative activity in which we detach from our thoughts. More nature connected people are more likely to have higher life satisfaction and wellbeing – and are more likely to take action in daily life which is environment and nature-positive.

Paper by James Farrell for ICF ICF Executive and Leadership Coaching Community of Practice – Wellbeing in Executive and Leadership Coaching Panel, 13 July 2023.

“Coaching leaders for wellbeing: The role of nature and value of ‘getting amongst it’“

For a PDF of this paper contact us.

‘Being in Nature – 20 practices to help you flourish in a busy world’ is available from the authors direct at https://natureconnectionbooks.com, or usual bookshops.

References

Mayer, F. S., & Frantz, C. M. (2004). The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24, 504–515.

Morton, T (2017) Humankind – Solidarity with nonhuman people. Verso, London.

Piff, P., Dietze, Feinberg, Stancato, Keltner (2015) Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. J Pers Soc Psychol 108 (6)

Plambech & C.Konijnendijk van den Bosch (2015) The impact of nature on creativity – A study among Danish creative professionals. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening Volume 14, Issue 2

Pritchard, A., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D. et al. (2020) The Relationship Between Nature Connectedness and Eudaimonic Well-Being: A Meta-analysis. J Happiness Stud 21, 1145–1167

Richardson, M., Hamlin, I., Elliott, L.R. et al. (2022) Country-level factors in a failing relationship with nature: Nature connectedness as a key metric for a sustainable future. Ambio 51, 2201–2213

Shultz, P. W. (2002). Inclusion with nature: The psychology of human-nature relations. In P. Schmuck & W. P. Schultz (Eds.), Psychology of sustainable development (pp. 61–78). Kluwer Academic Publishers

UNEP & IUCN (2021) United Nations Environment Programme and International Union for Conservation of Nature – Nature-based solutions for climate change mitigation. Nairobi and Gland.

Weinstein, N., Andrew K. Przybylski & Richard M. Ryan (2009) Can Nature Make Us More Caring? Effects of Immersion in Nature on Intrinsic Aspirations and Generosity. PSPB, Vol. 35 No. 10